As opera developed, libretti (or librettos: libretti is the plural in Italian, librettos sounds more natural in English even though it's an Italian word) were written less as poetry and more as prose, with the poetry concentrated in the arias. The words and music need to change metre and rhythm according to the mood of the characters and to prevent repetition and boredom. For example, a character who is angry may sing in short brief musical lines, so the poetry needs to be in similar short bursts, perhaps with half-rhymes. A character singing of love may sing in longer, more expansive musical lines and needs a lyrical poetry to match this.

In Puccini's team, Luigi Illica wrote the basic scenario of the opera and Giuseppe Giacosa wrote the poetry.

|

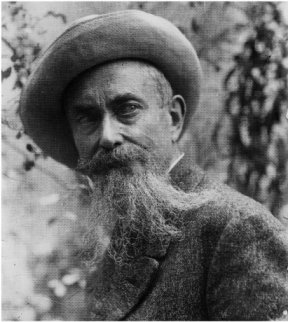

Puccini, Giacosa, Illica

Both librettists were accomplished men in their own right but are by far best known for their collaborative work with Puccini. Other celebrated composer/librettists are Mozart/da Ponte (Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, Cosi fan tutte), Verdi/ Boito (Otello, Falstaff), Strauss/ von Hofmannsthal (Elektra, der Rosenkavalier and more) and Wagner/ Wagner (yes, Wagner wrote both music and words to his operas). Incidentally, Illica apparently lost his right ear in a duel over a woman, which is why it never appears in a photograph:

Recondita armonia How strange the harmony

di bellezze diverse! of contrasting beauties!

E bruna Floria Floria is dark,

l'ardente amante mia she is my passionate lover

(Floria is Tosca's first name.) Each line has six syllables and ends with a rhyme (the half-rhyme of armoniA with diversE might indicate the harmonious contrast: almost the same, but different). Puccini's music keeps the first two lines simple, wondering, the notes are pretty much the same; the second two lines though have more musical jumps, more melody, as if the thoughts of Tosca make Cavaradossi more inspired.

One of the more effective lines in Tosca comes when the villain, Baron Scarpia, is describing how he is torturing Cavaradossi with a ring of steel:

che ad ogni niego ne sprizza sangue senza merce: that spurts blood mercilessly at each denial

The repeating s/z sounds match well the meaning of spurting blood. I suspect Giacosa was quite pleased with that one. By contrast, I suspect the following is Illica's. It is pure plot exposition, is rather clumsy (and very full of consonants), and Puccini rather throws up his hands and has nothing to do with it, Cavaradossi being left to rattle off the line as quickly as possible on the same note:

Angelotti! Il Console della spenta repubblica romana!: Angelotti! The consul of the fallen Roman republic!

Let's finish with Placido Domingo again, singing Recondita armonia in a live film version, shot in the exact locations and times of the opera in 1992. Listen to the opening stanza as described above and see if you can follow the lyrics:

Recondita armonia

di bellezze diverse!

E bruna Floria

l'ardente amante mia.

E te, beltade ignota

cinta di chiome bionde!

Tu azzuro hai l'occhio

Tosca ha l'occhio nero!

L'arte nel suo mistero

il mio solo pensiero,

il mio sol pensier sei tu!

Tosca, sei tu!

E te, beltade ignota

cinta di chiome bionde!

Tu azzuro hai l'occhio

Tosca ha l'occhio nero!

L'arte nel suo mistero

le diverse bellezze insiem confonde:

ma nel ritrar costei il mio solo pensiero,

il mio sol pensier sei tu!

Tosca, sei tu!

I learned things today. Such as Arias don't have titles. Many other things but I'll go on forever with that. I'll just say it's almost as passionate an explanation as when "La Mamma Morta" was explained to Joe by Andrew in Philadelphia. At this rate I'll need this in book form so I can take it with me.

ReplyDeleteAnother interesting blog :-)Can I request one about the technical stuff (pretty please). Having had several discussions about singers technique (breathing, different 'voices'and the bridge between them (have forgotten the actual term for it))..I have to admit I'm none the wiser...

ReplyDeleteAlso can you include some info about different musical terms...(diminuendo, cadenza, leitmotif etc)

cheers x

Kath: Good idea. I'll try and post something in a couple of days.

ReplyDeleteWatched first opera vid - Tosca w AG, JK and BT. Loved it. Thank you for the link. Have plot questions, but don't know that they matter (Scarpia is a broken and a bad guy, but why?)

ReplyDeleteSome other questions then:

1. Is it an 'aria' regardless of whether a male or female sings it?

2. Are most of the operas written with a tenor or soprano in mind, and the bass-baritone is a secondary role?

3. The conductor - Tosca was amazing for the orchestra performance as much as the singers. Does each conductor interpret the original music his or her own way, and how much does that control what the singer does?

The part in Act 3 where AG and JK sing without the orchestra is amazing, now that you pointed it out. Is that a decision made by the conductor?

4. Seemed BT did a lot of acting with facial/body expressions, whereas JK did it with the incredible nuances of his voice. Had a much more emotional impact.

5. Why did T leave her cross with S's body?

6. The info you provide in this post, re the poetry of the opera, is very helpful. Do you recommend knowing the major parts of an opera this way before viewing?

Sorry I got a bit long here, but this Tosca was very good, lots of questions swirling.

Hi Sunny,

ReplyDelete1. Yes. An aria is a piece of music for solo voice (usually with a discernible melody), regardless of who sings it.

2. Yes. And no. In early operas, the heroic part was taken by a castrato: yes, a boy castrated before his voice had broken so that as a man, he retained this high voice. Towards the end of the 18th century, the natural tenor voice took over as the voice of the hero and lover (this is explored in Rolando's "What makes a great tenor?" documentary). In the vast majority of love stories, the tenor is almost always in love with the soprano. The tenor is young; the tenor is the hero.

In contrast, baritones and basses have a much more varied repertoire. Being lower voices, they often play older or authority figures: kings, fathers. They can be the tenor's trusted friend (like Marcello in La Boheme or his rival in love (like Scarpia in Tosca): in fact the soprano-tenor-baritone love triangle is quite common. They are villains (Tosca again). There are many operas where the baritone/ bass is the leading character. In fact in both Mozart's Figaro and Don Giovanni (see Thomas Allen post), it is the tenors who are secondary.

3. Yes, each conductor will form his own interpretation of the music based on the score: how loud is "loud"? How fast is "fast"? How long is a "pause"? He should work closely with the singers to agree an approach. In performance, he is there to guide and support them. If a singer is having a particularly good day, for example, he may hold a note for longer than in rehearsal; or he may need extra time to breathe; he may be struggling with volume so the orchestra needs to be quieter (or louder to cover up mistakes!); he may have to fiddle with a prop etc

The unaccompanied section is unaccompanied in the score: it is marked to be sung "with great enthusiasm". The staging is down to the director/producer to be agreed with the singers and conductor.

4. In a large theatre, the voice will carry more than the face. And as we're dealing with music, it's the musical expression that probably matters most. In today's internet, television, HD broadcast age, singers are incredibly aware of the importance of being able to act convincingly: some are invariably better than others. I respond to JK because I'm always listening for what he does with his voice: I know the notes and the music; the interesting thing is what each singer does to those notes to make them unique.

5. Tosca is a religious woman as is made clear from her first appearance, her outburst "You'll not have him tonight!" that shocks Scarpia for being uttered in church, and her prayer. After she has killed Scarpia she says: "He is dead. Now I forgive him." Leaving her cross is a blessing on Scarpia and perhaps, a symbol of atonement for killing him.

6. It's always useful to know as much as you can about the libretto. This site could be useful:

http://www.aria-database.com/

also: http://www.opera-guide.ch/index.php?uilang=en

Try and learn the words of key arias. It will help you find your place in the performance and to fully appreciate what the singer is doing. I may not be fluent, but thanks to opera I can say "I love you" in at least five languages (and know the wording of a safe conduct pass if I ever get stuck in an authoritarian Rome).

Thank you! This is great information, and helps tremendously. The two links are excellent, and I'll use them. Even now, knowing just a bit of the libretto makes a difference in appreciating.

ReplyDeleteFive, eh? And safe conduct! Most useful!